An Antidote to Negativity

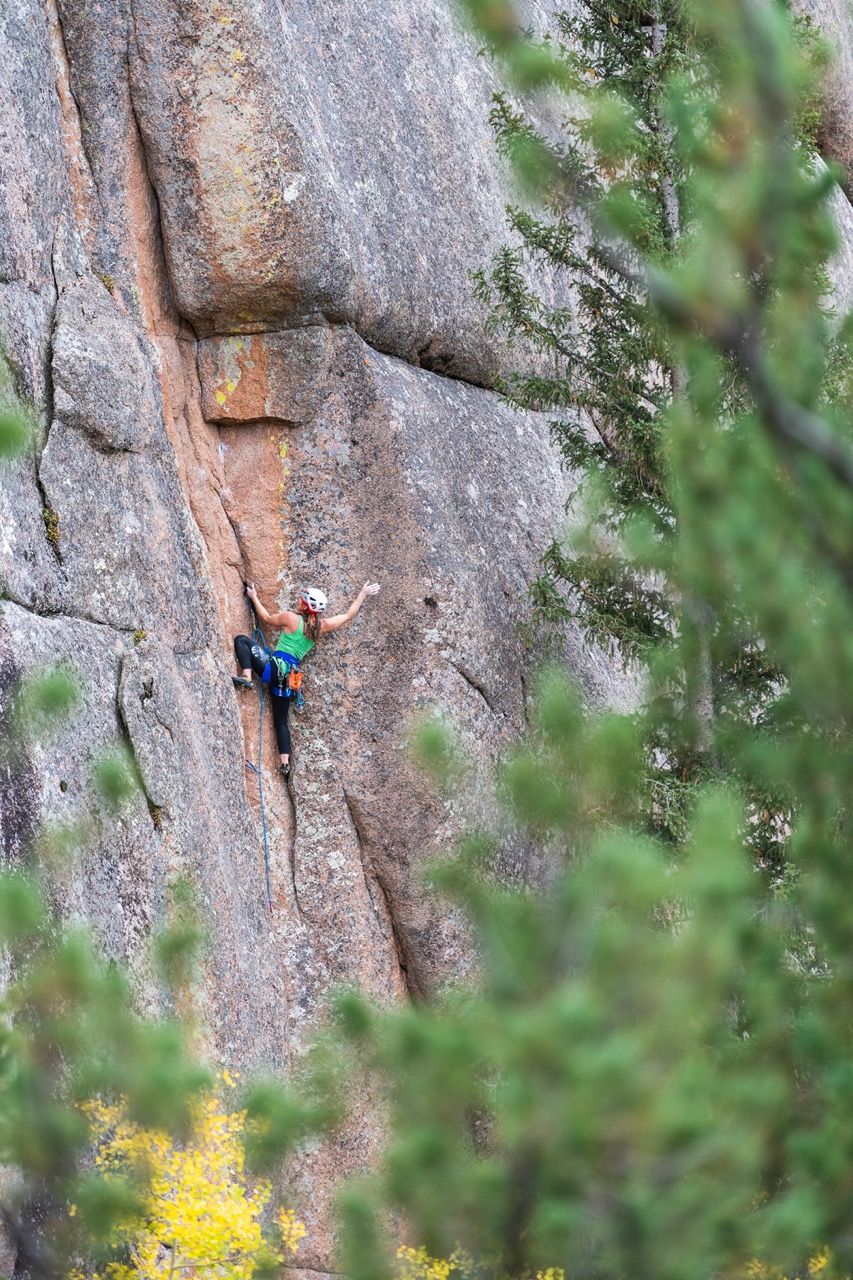

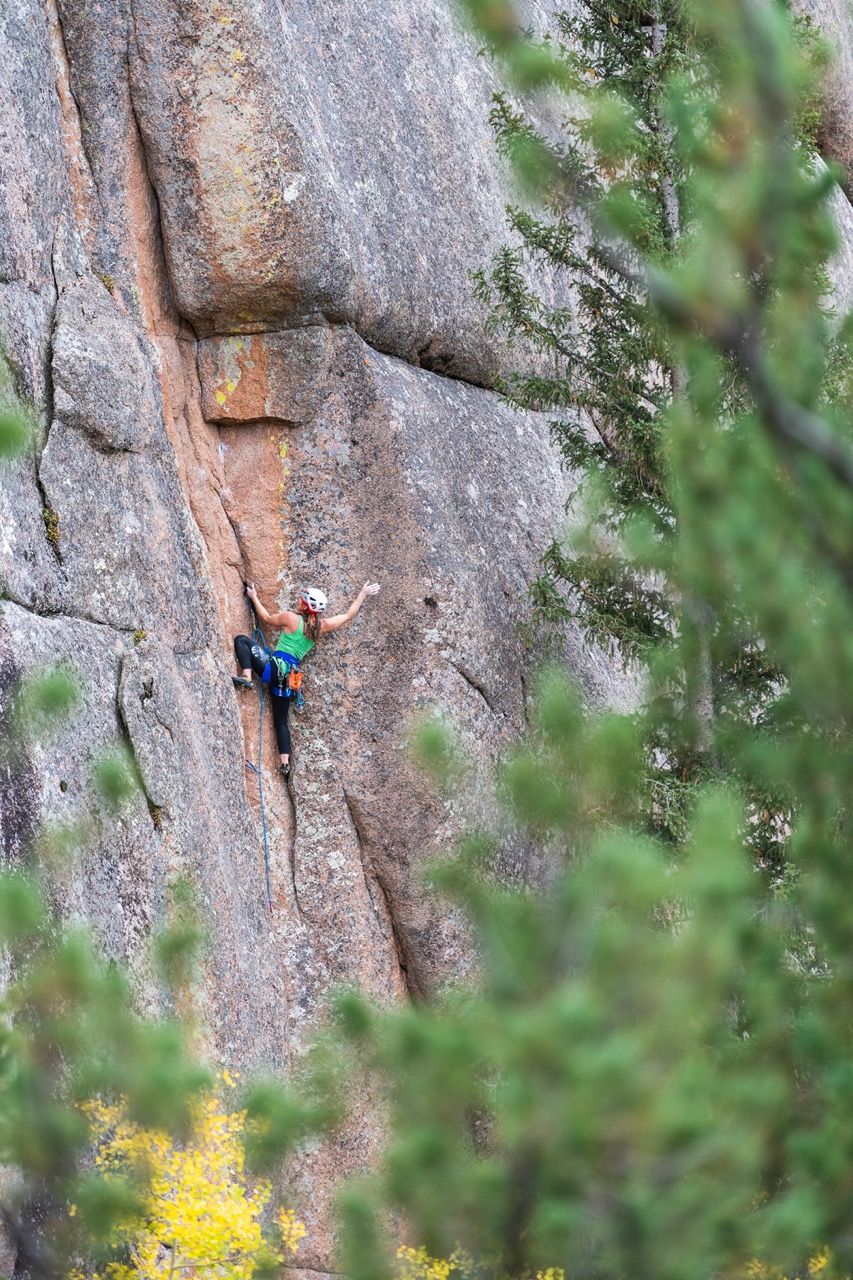

Mustering every ounce of focus and precision, I lunge toward the tiny, sloping edge. Barely grasping it, I let out a yell, willing myself to hold on. I reel my body in, placing my feet, then execute the final moves of the crux sequence, barely. Onto the easier climbing, I work to regain composure. I give a few shakes attempting to recover from the pump in my forearms, breathing deeply. Then into the final difficult (but not AS hard) sequence. My body is shaky, tired. I feel the anxiety begin to creep in. Internally, but loudly, the thoughts proclaim doubt at my ability to continue. I will myself to focus, to keep moving. Everything goes smoothly… until the last move. As I raise my feet to set up for the long reach – where I had fallen on several previous attempts – my fingers, curled around yet another tiny edge, begin to open. Then in the split of a second, I’m sailing through the air and dangling in my harness.

“Dammit!” escapes my lips. Internally, I am tempted to begin berating myself…

Anxiety undermines focus. Frustration follows “failure.” It happens to most of us. Probably you too. But I’m gonna call you out here: anxiety and frustration have less to do with your actual performance and more to do with the intention (or lack thereof) in your climbing process.

There are an infinite number of positives and negatives that you can discover when you analyze a specific climbing performance. Analysis is good, it’s how you learn. But when you overly identify with the negative aspects of one specific past or future performance – causing anxiety or frustration – it’s usually because you’re neglecting to take in the big picture of your climbing. The good news is, you can address this issue by defining your goals and consistently directing your focus towards your goals.

You might be thinking: “But Josie, I know what my goals are and the anxiety and frustration are about not achieving them!” But hear me out. We need to go further below the surface in the process of defining goals – from a big picture down to a detailed perspective. In order to manage your anxiety and frustration, it helps to clearly articulate three things in any given moment of climbing:

1. This is who I am as a climber ________________

2. This is what I’m working towards ________________

3. This is how I’m trying to do it now _______________

Let’s think of the above three statements – the who, what and how – as three types of goals, respectively: purpose, specific goals and clear intentions. Why are these important? Well, what we’re really trying to do is improve our overall motivation in climbing. Defining your identity as an athlete, what you’re working towards in climbing and the clear – in this present moment – intentions, increases your control over achieving success. Every little success causes the brain to reward us with dopamine, which increases focus and motivation. Focus and motivation lead to more success. Consistent success over time is what creates the momentum to stay motivated and positive when doing the hard things that are required for us to be the climbers we want to be (assuming that you don’t climb because it’s easy!). When we’re being the climbers we want to be, concern over isolated past and future performances have very little impact on our experience.

Defining who you are as a climber is about articulating the big picture of what you want to get out of climbing, what you love about it, why you do it: your “purpose.” This becomes the overall goal of how to approach rock climbing, day in, day out. For example, I climb for the feeling of being immersed in a playful experience of moving my body over rock. I love the challenge of puzzling through hard moves, of pushing my body to continue to hold on, even when I’m pumped or scared. I climb because it forces me to be present and it teaches me something new everyday. Knowing these things allows me to also know that I am succeeding in rock climbing, just by being present in moving my body over rock. And, importantly, it allows me to acknowledge that I am accomplishing my purpose in climbing by challenging myself, by getting pumped and scared, by learning – all things that, if looked at from a different perspective, could be labeled as “failure” instead of “success.”

Defining what you’re working towards is the more standard version of goals. I like to think about several categories within specific goals: performance, training and skills, and within each of these categories are short-term and long-term goals. A good formula in creating these goals is to start with long-term, performance goals, then think about training, skills and shorter-term performance goals that help build towards the longer-term goals. When selecting long-term goals, think about how they align with the big picture of why you climb. This helps maintain focus in training because you’re moving toward something that is truly inspirational, while also maintaining motivation by being able to check off specific, smaller successes along the way.

Finally, define clear intentions for how you’re trying to work on climbing in each session, each route or boulder problem. Intentions also build toward your specific goals, but have one very important element: intentions are process (how) oriented rather than outcome oriented. An intention could be something like focusing on moving smoothly through a sequence, refining beta, trying to relax more in a spot that scares you, etc., rather than intending to send your project on this go. This allows you to succeed whether you send or not. This has the twofold benefit of reducing performance anxiety before a redpoint attempt and reducing frustration if you fall.

To talk about your goals or to not talk about your goals? There are two schools of thought on this topic. One side recommends sharing your goals because it helps to have others to hold you accountable and keep you motivated. The other side recommends to stay quiet about your goals. When you talk about your goals, your brain gives you the reward of dopamine as if you’ve actually accomplished the goal, so you don’t actually have to work for it, which actually decreases your motivation. To answer this question then, I recommend thinking about why you want to share your goals. We usually need a partner for our climbing goals, so it might help to share your goals with the people that will go out and work on a project with you. It might also help to share if you need a reminder of your intentions to keep you from getting too outcome focused. Share your goals if you need support. But share your goals with discretion, not just because you want to spray about what you're working on!

How it works in practice:

You created a training plan based on a long-term goal. This specific goal inspires you because it has fun movement, a runout that challenges you to focus, a technical crux right at the end to test your endurance. You identify as a climber that appreciates both physical and mental challenge. You love the idea of this project, because one of the things you value about climbing is how it teaches you to manage your stress. Your training includes working on a short-term project that involves similar elements as your long-term project, but it’s a little easier.

You worked out the beta on the short-term project last weekend and think you could probably send today. The pressure is on and you start to feel anxious. Before you leave the ground your climbing partner reminds you that your intentions are to focus on moving smoothly through the first sequence and relaxing through the runout that scared you last week, because you know it’s safe.

Because you’re less focused on the pressure to send, you're able to relax and climb more smoothly through the first crux. You get to the runout and are still scared. You remember the intention was to relax, but it’s too late: you’ve been over-gripping and you’re already too pumped to do the final move. You think momentarily about down climbing, but again your belayer reminds you: the fall is safe. You decide to go for the move. You fall. It’s fine.

For a split second you feel the familiar frustration arise, ready to start the mental flogging because you “got scared unnecessarily, blowing the send.” But then you remember what your intention was and you have just done exactly what you needed to do: taught yourself that the fall is safe, so next go you can relax. Not only that, but part of why you chose this climb is because you wanted to get better at climbing through runouts for your long-term project. Now you know that part of refining the beta is to actually take falls (as long as they are safe!), so you don’t use extra energy next time. Then you remember that you value the way climbing teaches you to respond under stress. You were able to try the move rather than just downclimb, so you are also able to recognize progress in this.

Overall, you’ve reduced performance anxiety and frustration. You found success and now you’re even more motivated to try again, curious to see how well you can relax through the runout. And you just feel psyched on the whole challenge: climbing is pretty awesome! You’re operating on a lot of dopamine. We’ll just call this legal doping – an antidote to negativity.

Follow Josie to see more of her adventures! @josie_mckee_.